Rising From The Caves

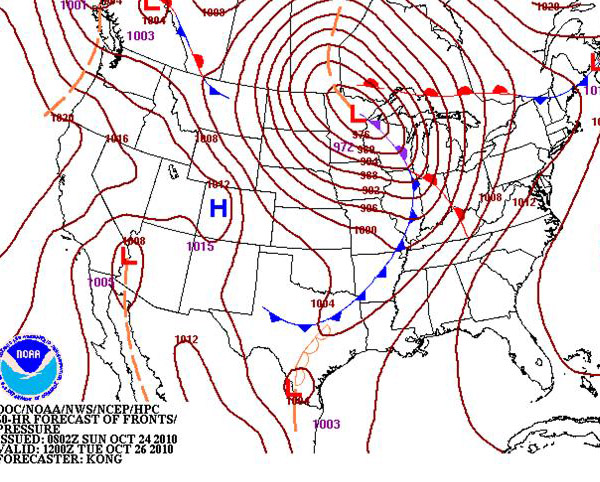

During the last week of October 2010, an intense low-pressure system moved from west to east across the mid-latitudes of North America. Local weather forecasters wondered whether it would become “the storm of the century” – a term that seems to get used practically every year. Indeed, the storm brought very strong winds and caused serious damage in a few areas. In the map below, showing a forecast for the morning of October 26, note the massive circulation around the low-pressure center. With winds moving counter-clockwise around a low, this situation produced strong, sustained southwest winds all the way from Texas to the Great Lakes.

In the wake of the storm, birders found Cave Swallows all over the northeastern U.S. and southeastern Canada, especially along the coast and around the edges of the Great Lakes. The map below, taken from the bird-finding app BirdsEye, shows a snapshot of some of the Cave Swallows that had been reported to Project eBird at the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology; this does not encompass all the reports, of course, but it gives a general idea of where the birds were found.

If you had predicted this Cave Swallow flight to an expert birder in 1970, they would have laughed in your face. To put this in perspective: Cave Swallow is a bird that nests no farther north than Texas. Prior to the late 1980s, there had been essentially no records anywhere in the area shown on the map just above. So to have hundreds of individuals scattered over dozens of sites this fall was a big shock, right?

Wrong. The most surprising thing about this swallow invasion is that it wasn’t surprising. Birders all over the northeast looked at the weather pattern and said, “There should be some Cave Swallows around,” and then went out and found them. In the space of a few short years, Cave Swallow invasions far to the northeast of their normal range have become an expected phenomenon of fall.

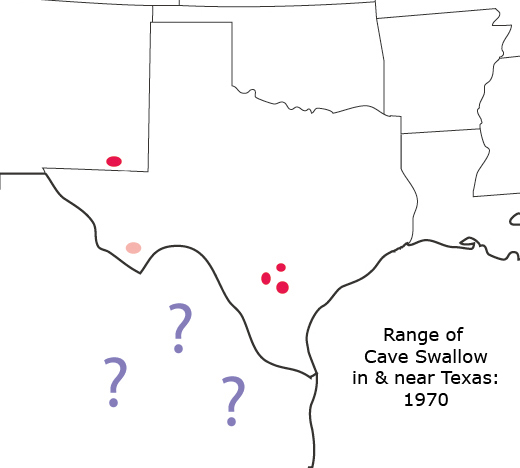

What has driven this stunning change in status? Basically, it was caused by a change in nesting behavior. As recently as 1970, Cave Swallows were known to nest at only a few sites in the U.S., all of them in (you guessed it) caves. The colony at Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico was easily accessible, but it took some work to get to any of the Texas sites. The map below shows the approximate U.S. nesting range in 1970, with red showing where the species was numerous in summer, pale red showing where it was less common in summer, and purple indicating the question of whether it was a year-round resident near caves in northern Mexico.

In those days, the Cave Swallows in the U.S. nested only inside caves, so their choices of nesting sites were naturally quite limited. But most species of swallows in the U.S. had adapted to manmade sites for building their nests. Cliff Swallow, a close relative of Cave Swallow, was an abundant nesting bird under bridges and in large concrete culverts all over Texas (the photo below shows Cliff Swallows at their mud nests under a bridge). Barn Swallows nested in these sites as well, so birders were accustomed to seeing lots of swallows flying around bridges.

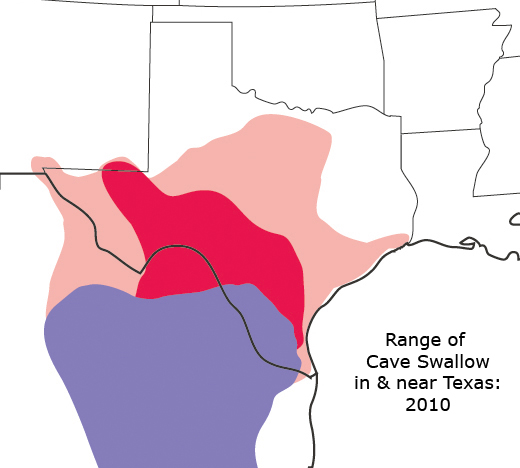

But in the mid-1970s, birders in Texas noticed something new: Cave Swallows were starting to nest under bridges as well. We’ll never know when they began to make this adjustment; probably they were doing it for a while before anyone noticed. But once we noticed, we found that the birds were in the middle of a massive range expansion. Year by year they spread to more bridges and culverts, and even started nesting in sheds and under picnic shelters. Here is the nesting range for Cave Swallow around 2010, again with red indicating where they are common in summer, pale red showing where they are uncommon in summer, and purple showing where they may be found year-round.

Within a few years, birders started finding Cave Swallows in fall far to the north: first around the well-watched hotspot of Cape May, New Jersey, and then at more and more places. Some friends and I found the first record for New York state in 1990, but now there are many records, some involving large flocks.

I firmly believe that the potential for this northward straying by Cave Swallows had been there for many decades. But until their nesting range and population went through a dramatic expansion, there were so few of them that such strays would have gone unnoticed. Even today, the birds are being found more and more simply because more birders are specifically looking for them. It makes me wonder: what’s the next big change in bird distributional patterns? Could it be that it’s happening already, and we just haven’t noticed?

Good summary, and I certainly agree that the large numbers reported in recent years are partly a result of more people searching specifically for Cave Swallows under appropriate conditions. But there’s still an element of mystery to the phenomenon – why is it that Cave Swallows are particularly prone to this northeastward drift in late fall? Sure, there’s typically a smattering of other southwestern species (especially flycatchers) reported in the northeast around the same time, but rarely in multiples, let alone large numbers. Maybe it’s partly that swallows are more gregarious than many others, but on the other hand Cave Swallow isn’t a particularly highly migratory species to begin with. If anything, given the extent of movements observed in fall, it’s a bit surprising that there haven’t yet been more widely scattered breeding records (though I suspect those will come before too much longer).