Journal Club: Polly gets his own cracker: clever cockatoo manufactures, uses tools | video |

SUMMARY: Not known to manufacture or use tools in the wild, a captive cockatoo demonstrates that parrots can make tools to suit their needs.

If you’ve ever lived with a parrot, then you are well aware that they come with a built-in multi-purpose tool attached to their faces. For this reason, most parrots do just fine without ever needing to create a separate tool to meet their objectives.

If you’ve ever lived with a parrot, then you are well aware that they come with a built-in multi-purpose tool attached to their faces. For this reason, most parrots do just fine without ever needing to create a separate tool to meet their objectives.

Well, usually. It turns out that at least one parrot, a captive cockatoo named Figaro, has found circumstances when his built-in Swiss army knife does not do the job, so he did what any self-respecting bird would do: he constructed a tool designed to get the job done.

Figaro, a captive male Tanimbar corella, uses a tool of his own making to retrieve a cashew nut.

[DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.002]

Figaro lives with a group of captive Tanimbar corellas in a large aviary at the University of Vienna in Austria. One day, a student caregiver noticed Figaro pushing a stone pebble through the aviary wire mesh, where it fell on a wood structural beam. Unable to retrieve the stone with his foot, Figaro then fetched a piece of bamboo and again attempted to retrieve the stone using the bamboo stick. Although he was ultimately unsuccessful, surprised researchers recognised the potential of his actions and immediately placed him in visual isolation from the group (in the company of a submissive female named Heidi) to avoid him sharing this novel behaviour with the rest of the flock.

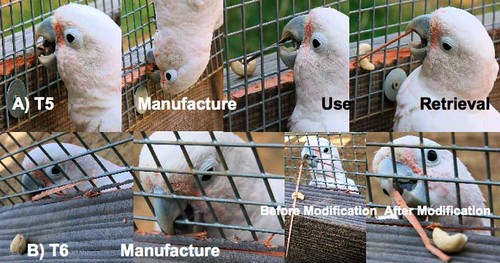

During the next three days, the researchers ran trials of the original scenario, which was repeated ten times but substituting a cashew nut for the pebble. All trials were captured on video and the process of tool manufacture and use was documented photographically (figure 1 or view larger):

Figure 1. Typical action sequence when manufacturing a larch splinter tool.

[DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.002]

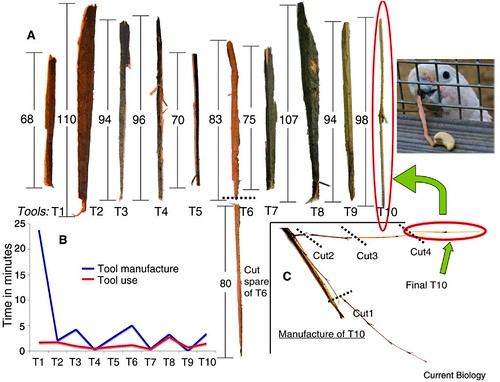

During these trials, Figaro used 10 tools, nine of which he manufactured and one of which was ready-made (figure 2 or view larger):

Figure 2. Manufacture and use of tools 1–10. (A) Tools used (T1–T10); tool length in mm; T1–T8 = splinter tools; T9 = bamboo tool; T10 = twig tool. (B) Blue: time for tool manufacture; red: time for tool use (from manufacture to retrieval) for each trial in minutes. (C) Manufacture of T10 using four sequential cuts.

[DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.002]

“We know that these animals are very smart but we were still surprised he was capable of making a tool”, wrote lead author, cognitive biologist Alice Auersperg, of the University of Vienna.

“For a long time such talents have only been attributed to our closest relatives, the great apes. Since then, however, tool use has been reported in capuchin monkeys, some birds and even some invertebrates”, explained Dr Auersperg in the paper.

Certainly, birds are no strangers to tool making. Betty the captive New Caledonian crow was the first bird to surprise researchers with her ability to create a hook from a piece of wire which she then used to retrieve food out of a pipe. Even though this species does use tools in the wild, Betty’s tool manufacturing abilities are still considered to be a striking example of individual creativity and innovation.

How Figaro discovered how to make and use tools remains unclear, and it shows that scientists still have much to learn about the roles of culture and ecology in promoting and supporting the evolution of innovative behaviour and intelligence.

“It is still difficult to identify cognitive operations”, explains co-author Alex Kacelnik, a Professor of Behavioural Ecology at the University of Oxford, in a press release.

It’s also difficult to know what role intelligence plays in the manufacture and use of tools.

“Figaro, and his predecessor Betty, may help us unlock many unknowns in the evolution of intelligence.”

Here’s the researchers’ video of Figaro’s tool manufacture and use trials:

[video link]

Sources:

Auersperg A.M.I., Szabo B., von Bayern A.M.P. & Kacelnik A. (2012). Spontaneous innovation in tool manufacture and use in a Goffin’s cockatoo. Current Biology, 22 (21) R903-R904. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.002

University of Vienna press release

NOTE: slightly reformatted from the original, which was published on The Guardian.

.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ..

Follow Grrlscientist’s work on facebook, Google +, LinkedIn, Pinterest and of course, twitter: @GrrlScientist

email: grrlscientist@gmail.com